Jacques Ibert (1890–1962)

Divertissement: Introduction, Waltz, and Finale

Ibert’s style is often called “eclectic,” likely because it defies being pigeonholed into any of the major “schools” of his twentieth-century colleagues—Schoenberg, Bartók, Debussy, Ravel, Hindemith, Stravinsky, etc. Rather, his compositions reflect a chameleon-like resourcefulness, suiting the music solely to the task and subject at hand with typical French balance of form, elegant and often witty melody, and colorful but transparent orchestration.

Divertissement is a 1930 rework of incidental music composed the year before for Eugène Labiche's The Italian Straw Hat, a theatrical farce about a nervous bridegroom, his hungry horse (who eats part of the straw hat) and a philandering wife—whose honor the bridegroom attempts to protect through misdirection and disguises—in a series of screwball vignettes. The music, which relates to the various people with whom the woman's straw hat comes in contact, is chock-full of unexpected rhythms, piano chords, and trumpets. Keep an ear out for the parody quotation of Mendelssohn’s well-known Bridle March—just one of the music’s many surprises which demonstrate that classical music doesn’t always have to be serious.

In Spring 1966, during the short trying time when the orchestra was split into two entities, George Perkins led the Midland Empire Chamber Orchestra in three performances of Ibert’s light-hearted work. The first performance of Divertissement by the Billings Symphony finally occurred on February 11, 1968, under the baton of Maestro Perkins.

Performance of this work by arrangement with Boosey and Hawkes, Inc., Sole Agent in the U.S., Canada and Mexico for Durand S.A. Editions Musicales, a Universal Music Publishing Group company, publisher and copyright owner.

Anne Bredon (1930–2019)

“Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You”

Originally written by folk singer Anne Bredon in the late 1950s, “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You” was first recorded by Joan Baez for her 1962 live album, Joan Baez in Concert. Just a session musician when he heard it, guitarist Jimmy Page began working the track and, during their first meeting July 1968, played it to Robert Plant. They then decided to record it together and even did the arrangement before Led Zeppelin was formed: “I knew exactly how that was going to shape up. I set the mood with the acoustic guitar and that flamenco-like section. But Robert embraced it. He came up with an incredible, plaintive vocal.” The song became the second track on the band’s 1969 self-titled debut album.

Formed in 1985 by RCA, the Grammy® nominated, Juilliard trained, largest selling string quartet in history, The Hampton (Rock) String Quartet [HSQ] forged new ground where now, hundreds of groups have followed. Tonight’s string arrangement by HSQ cellist (and principal arranger) John Reed is the quartet’s “favorite serious work”—“real meat and potatoes.”

Mily Balakirev (1836–1910)

Islamey

One of the key figures of 19th-century emerging Russian nationalism and the prime motivator in the so-called “Mighty Handful,” Mily Balakirev was influential in conducting the new works of Borodin, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Cui, as well as his own. His most famous piece is the virtuoso piano composition, Islamey.

Written in September 1869, Islamey is based on two folk themes. The first is a quick dance-tune from the Caucasus in southern Russia and is full of energy and rapid repeated notes. This theme governs the whole of the first section of the piece, and much of the third. As a contrast, the middle section uses a love song from the Crimea, in southern Ukraine. This romantic melody is transformed into a lively Trepak dance towards the end of the work.

Although the subtitle “Oriental Fantasy” is misleading in this decidedly Russian work, it displays Balakirev’s original and highly influential brand of Russian exoticism, so apparent in such later works as Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade and Borodin’s Prince Igor. Too often heard as a brittle, vacuous display piece, this orchestration of Islamey aims to keep the virtuoso nature of the work, while filling it with folk-like Russian color. — Notes adapted from arranger Iain Farrington

Jean Sibelius (1865–1967)

Kuolema: Valse triste

Originally incidental music for his brother-in-law Arvid Järnefelt’s 1903 play, Kuolema, Valse triste is today far better known as a short concert piece which sets the following scene with or without actors:

“It is night. The son, who has been watching beside the bedside of his sick mother, has fallen asleep from sheer weariness, Gradually a ruddy light is diffused through the room: there is a sound of distant music: the glow and the music steal nearer until the strains of a valse melody float distantly to our ears. The sleeping mother awakens, rises from her bed and, in her long white garment, which takes the semblance of a ball dress, begins to move silently and slowly to and fro. She waves her hands and beckons in time to the music, as though she were summoning a crowd of invisible guests. And now they appear, these strange visionary couples, turning and gliding to an unearthly valse rhythm. The dying woman mingles with the dancers; she strives to make them look into her eyes, but the shadowy guests one and all avoid her glance. Then she seems to sink exhausted on her bed and the music breaks off. Presently she gathers all her strength and invokes the dance once more, with more energetic gestures than before. Back come the shadowy dancers, gyrating in a wild, mad rhythm. The weird gaiety reaches a climax; there is a knock at the door, which flies wide open; the mother utters a despairing cry; the spectral guests vanish; the music dies away. Death stands on the threshold.” (translation of the play’s original program notes)

Georges Bizet (1836–1975)

Children’s Games: Galop (The Ball)

Originally written for piano four-hands, Bizet’s 1871 suite is full of melody, brilliance, and charm. Twelve miniatures in all—including The Swing, The Spinning Top, Soap Bubbles and Leap Frog—represent various children’s activities. The Ball finishes off the suite with a spirited galop, a two-step dance popular in Bizet’s day.

James Alan Hetfield (b. 1963) and Lars Ulrich (b. 1963)

“Nothing Else Matters”

Feeling homesick and missing his then-girlfriend while on tour, Metallica’s lead vocalist James Hetfield was hesitant to play his new composition for his band mates, considering it “too soft” for the band’s heavy metal genre and style. Drummer Lars Ulrich, however, was impressed by “Nothing Else Matters” and suggested the band should work on the piece. Producer Bob Rock also saw the potential, but felt the song needed a bigger sound, advising them to add a string section to the song. The band agreed, and composer Michael Kamen (1995’s Mr. Holland’s Opus) was asked to write the orchestral arrangement, providing the large sound “Nothing Else Matters” needed.

The song was eventually released on the band’s self-titled fifth studio album Metallica (often referred to as The Black Album) and despite initially displeasing Metallica fans with its commercial ‘non-metal’ sound, the song’s relative softness became a bridge to new fans outside the heavy metal genre, especially in Europe where it was a top-10 hit in most countries. The Black Album would eventually sell over 17 million copies in the U.S., and “Nothing Else Matters” was the Metallica’s first music video to surpass a billion views on YouTube.

Darius Milhaud (1892–1974)

The Creation of the World

A London performance by Billy Arnold’s Novelty Jazz Band so sparked Milhaud’s fascination with American jazz, that when the French composer traveled to the U.S. in 1922 on a multi-city concert and conducting tour, he made it a point to frequent the black jazz clubs in Harlem, steeping himself in the music, its instrumentation and style. Upon his return to Paris, Milhaud took up a commission to compose a ballet based loosely on the African creation myths in Blaise Cendrar’s (1887–1961) L’anthologie nègre.

The Creation of the World debuted on October 25, 1923, at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées—which ten years earlier had seen the divisive premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s (1882–1971) The Rite of Spring. While not as riot-provoking, with its cumbersome costumes and mechanical choreography, The Creation was still more a succès de scandale than a true success. Milhaud’s score was initially blasted for not having much to do with the story, but just as the composer predicted to his friends and colleagues, the critical reaction turned to acceptance within a year, and to praise and recognition within a decade.

The ballet itself is nowadays revived but rarely—more of a curiosity than anything else—while Milhaud's music continues to be programmed, the earliest and one of the most successful uses of the jazz idiom by a classically trained composer.

Performance of this work by arrangement with Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey and Hawkes company, Sole Agent in the U.S., Canada and Mexico for Editions Max Eschig, © Editions Durand, Paris (Universal Music Publishing Group), publisher and copyright owner.

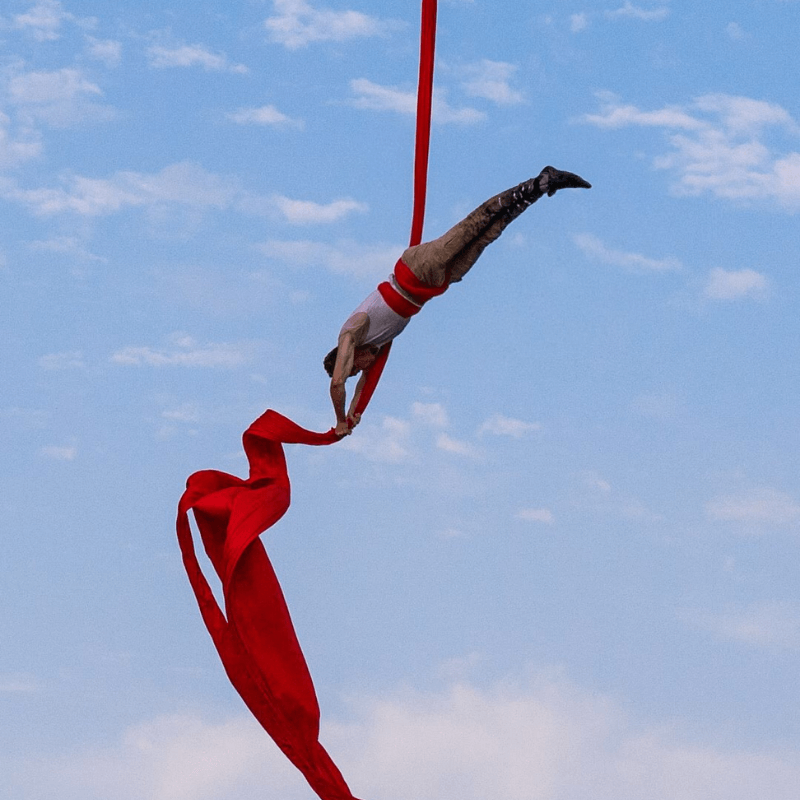

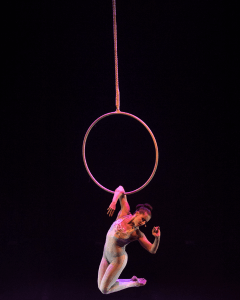

Any Riwer & Ron Oppenheimer

Forgotten Reasons

Before its orchestration by Erica Porter for a March 2023 performance with the Battle Creek Symphony (Maestra Harrigan’s “other” orchestra), cirque artist Ron Oppenheimer and composer Any Riwer originally titled their co-creation, Deep Soul.

“Sometimes in life, you get hurt again and again and find yourself in a dark place. You lose sight of all your passions, motivation disappears, and you isolate yourself from what you love most. Forgotten Reasons tells a story of rediscovery and healing. It is a journey of ups and downs, as well as the challenges you experience along the way, towards growth and finding one's self.” – Ron Oppenheimer

Pete Townshend (b. 1945)

“Who Are You”

The title track on The Who’s 1978 album, “Who Are You” is based on a day in the life of Pete Townshend: "Eleven hours in the Tin Pan, God, there's got to be another way." The “Tin Pan [Alley]” is Denmark Street in London’s West End, where Townsend had an excruciatingly long meeting over royalties, which made the entire band solvent millionaires for the first time. "I used to check my reflection, jumping with my cheap guitar, I must have lost my direction because I ended up a superstar.” Conflicted over fears of selling out, Townsend wandered to a Soho music club and proceeded to get completely drunk. At the club he ran into Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols, icons of the new punk rebellion and, in Townsend’s mind, everything he had left just left behind: idealism, politics, the voice of youth. Exacerbated, he stumbled from the bar and passed out in a random doorway. “A policeman knew my name,” and being kind, woke him and told him, “You can go sleep at home tonight, if you can get up and walk away.” Townsend’s response: “Who are you?”