Events

Classic Series

Pictures

Saturday

Sep 25, 2021

7:30 PM

Alberta Bair Theater

$18-$63

Gabriela Martinez piano

Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition

Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Gabriela Martínez performs Rachmaninoff’s popular Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition showcases the brilliant colors of the Billings Symphony Orchestra, providing a scenic backdrop for artwork by Lockwood elementary students.

GABRIELA MARTINEZ | PIANO

Versatile, daring, and insightful, Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Martinez is establishing a reputation on both the national and international stages for the lyricism of her playing, her compelling interpretations, and her elegant stage presence.

Versatile, daring, and insightful, Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Martinez is establishing a reputation on both the national and international stages for the lyricism of her playing, her compelling interpretations, and her elegant stage presence.

Delos recently released Ms. Martinez’s debut solo album, Amplified Soul, which features a wide-ranging program including works by Beethoven, Rachmaninoff, and Szymanowski. She also pays homage to acclaimed composers Mason Bates and Dan Visconti, whose title selection, Amplified Soul (world premiere recording), was written for her. Ms. Martinez collaborated with Grammy Award-winning producer David Frost on the recording. A music video of Amplified Soul can be found on Ms. Martinez’s YouTube Channel.

Since making her orchestral debut at age 7, Ms. Martinez has played with such distinguished orchestras as the San Francisco, Chicago, Houston, New Jersey, Tucson, West Michigan, Pacific, and Fort Worth symphonies; Germany’s Stuttgarter Philharmoniker, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, Nurnberger Philharmoniker; Canada’s Victoria Symphony Orchestra; the Costa Rica National Symphony and the Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra in Venezuela. Recent season highlights include debut appearances with the Buffalo, Boulder, Dayton, and National philharmonic orchestras and the Jacksonville, Delaware, Akron, La Crosse, Modesto, Rogue Valley, Springfield (MO), Topeka, and Wichita symphony orchestras.

She has performed with Gustavo Dudamel, James Gaffigan, James Conlon, Marcelo Lehninger, and Guillermo Figueroa, among many others, and has performed at such esteemed venues as Carnegie Hall, Avery Fisher Hall, Merkin Hall, and Alice Tully Hall in New York City; the Broad Stage in Santa Monica, El Paso Pro Musica Series, the Kansas City Harriman-Jewell Series; Canada’s Glenn Gould Studio; Salzburg’s Grosses Festspielhaus; Dresden’s Semperoper; Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens; and Paris’s Palace of Versailles. Her festival credits include the Mostly Mozart, Ravinia, and Rockport festivals in the United States; Italy’s Festival dei Due Mondi (Spoleto); Switzerland’s Verbier Festival; the Festival de Radio France et Montpellier; and Japan’s Tokyo International Music Festival.

Her wide-ranging career includes world premieres of new music, live performance broadcasts, and interviews on TV and radio. Her performances have been featured on National Public Radio, CNN, PBS, 60 Minutes, ABC, From the Top, Radio France, WQXR and WNYC (New York), MDR Kultur and Deutsche Welle (Germany), NHK (Japan), RAI (Italy), and on numerous television and radio stations in Venezuela.

Ms. Martinez was the First Prize winner of the Anton G. Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Dresden, and a semifinalist at the 12th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, where she also received the Jury Discretionary Award. She began her piano studies in Caracas with her mother, Alicia Gaggioni, and attended The Juilliard School, where she earned her Bachelor and Master of Music degrees as a full scholarship student of Yoheved Kaplinsky. Ms. Martinez was a fellow of Carnegie Hall’s The Academy, and a member of Ensemble Connect (formerly known as Ensemble ACJW), while concurrently working on her doctoral studies with Marco Antonio de Almeida in Halle, Germany.

PROGRAM NOTES

Written by BSOC Librarian Lisa Bollman.

MODEST MUSSORGSKY (1839–1881) | PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION

A half-century before the “French Six” there were the “Russian Five,” a group that included Modest Mussorgsky. Dubbed by art critic Vladimir Stassov the “Mighty Handful,” they were the musical wing of the nationalist movement that swept through the arts in Russia during the last half of the nineteenth century. The Five were mostly part-time composers, holding positions as minor bureaucrats and military officers. Only Rimsky-Korsakov eventually became a full-time music professor and composer.

A half-century before the “French Six” there were the “Russian Five,” a group that included Modest Mussorgsky. Dubbed by art critic Vladimir Stassov the “Mighty Handful,” they were the musical wing of the nationalist movement that swept through the arts in Russia during the last half of the nineteenth century. The Five were mostly part-time composers, holding positions as minor bureaucrats and military officers. Only Rimsky-Korsakov eventually became a full-time music professor and composer.

Among the Russian nationalists in other arts was the architect-artist Victor Hartmann, a close friend of Mussorgsky. Hartmann died of a heart attack in 1873, at the age of 39. The following year Stassov arranged a memorial exhibition of Hartmann’s drawings and watercolors. Mussorgsky, who had been devastated by his friend’s sudden death, attended the exhibition and was inspired to use some of the works displayed as the basis for a suite of piano pieces. Hartmann’s art encompassed architectural designs, theatrical scenery and costumes, designs for craftwork, studies of outstanding buildings, and scenes and portraits of everyday life. All these are included in Mussorgsky’s music.

Although Mussorgsky did perform Pictures at an Exhibition publicly, the work wasn’t published until 1886, five years after the composer’s death. Even then it remained almost unknown until 1922 when legendary conductor and patron of new music Serge Koussevitzky had the idea of commissioning French composer Maurice Ravel to make an orchestral arrangement. Ravel took quickly to the task, and Koussevitzky led the work premier of the new Mussorgsky-Ravel Pictures in Paris on May 3, 1923. It was an immediate hit, and while others have tried their hands at orchestrating the work—including Leopold Stokowski, Henry Wood, and Vladimir Ashkenazy—it is Ravel’s arrangement that has become a fixture in the orchestral repertoire.

The suite is in fifteen sections, with little to no breaks in between:

Promenade. A solo trumpet states for the first time a theme which recurs throughout the suite. Vladimir Stassov described the theme: “The composer here portrays himself walking now right, now left, now as an idle person, now urged to go near a picture; at times his joyous appearance is dampened as he thinks in sadness of his dead friend…”

Gnomus. This dark little piece was inspired by a Hartmann design for a carved wooden nutcracker in the shape of a gnome.

Promenade. A more contemplative version of the theme is heard.

Il vecchio castello (The Old Castle). As a student, Hartmann traveled to Italy, where he made a drawing of a lonely troubadour in front of a castle. Here the alto saxophone sings the troubadour’s sad song.

Promenade. This time, the theme has a heavier, more ponderous feeling.

Tuileries. This bright and lively section was inspired by a Hartmann watercolor of children at play in the famous Tuileries Garden in Paris. Woodwinds depict the “Dispute of the Children after Play,” as Mussorgsky subtitled the piece.

Bydlo. On a visit to Poland, Hartmann painted an old peasant wagon with large wooden wheels drawn by oxen (“bydlo” is Polish for “cattle”). The tuba introduces the main melody, which builds to a loud, percussive climax, then dies out as the wagon moves into the distance.

Promenade. This time we hear a quiet and tranquil version of the theme for winds and low strings.

Ballet des Petits Poussins dans leurs Coques (Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells). This playful music was inspired by a sketch—depicting a small child wearing the costume of an egg, with only head, arms, and legs sticking out—that Hartmann made for a children’s ballet.

Samuel Goldenburg and Schmuyle. Mussorgsky’s original title for this piece, inspired by a pair of Hartmann character sketches, was “Two Jewish Men; one rich, the other poor.” Goldenburg’s speech is weighty and pompous, and Schmuyle’s chattering response comes from the solo trumpet.

Limoges: Le Marché. Hartmann’s paining of the marketplace at Limoges depicts a group of women gossiping and quarreling. Mussorgsky amusingly imagined their conversation: “Great news! M. de Puissen-geout has just recovered his cow, The Fugitive. But the good crones of Limoges are not entirely agreed about this, because Mme. De Remboursac just acquired a beautiful new set of teeth, whereas M. de Panta-Pantaleon’s nose, which is in the way, remains the color of a peony.”

Catacombæ: Sepulchrum Romanum (Catacombs). The mood suddenly darkens, as Mussorgsky evokes a drawing Hartmann of himself, a friend, and a guide with a lamp exploring the underground catacombs of Paris.

Cum mortuis in lingua mortua (With the Dead in a Dead Language). The gloom of the previous tableau continues, with an ominous variant of the Promenade theme. Alongside his dodgy Latin, Mussorgsky wrote in the score: “The creative spirit of the departed Hartmann leads me to the skulls, calls out to them, and the skulls begin to glow dimly from within.”

La Cabane de Baba-Yaga sur des Pattes de Poul (The Hut on Fowl’s Legs). This dramatic tone poem depicts Baba-Yaga, the legendary Russian witch who eats human bones ground up by a mortar and pestle. She also uses her mortar to fly through the air, and Mussorgsky suggests this flight in his music. Hartmann’s original drawing was a design for a clock in the shape of Baba-Yaga’s hut, which is mounted on the legs of a fowl.

La Grande Porte de Kiev (The Great Gate of Kiev). Without a break, Mussorgsky moves into this impressive final movement, inspired by the drawing, “Project for a City Gate,” Hartmann’s entry in an architectural competition for a new gateway for the city of Kiev in honor of Czar Alexander II’s escape from assassination in April 1866. In the drawing, one sees two columns, one with a cupola suggesting the shapes of an ancient Russian helmet. Below them are prancing horses and an assemblage of people, which may have given Mussorgsky the idea for the processional-like feeling of this music, which builds to a grand and awesome climax.

Each BSO conductor programmed Pictures at least once during their tenure: Robert Staffonson (1955), George Perkins (1969), Uri Barnea (1986, 2002), and Anne Harrigan (2009).

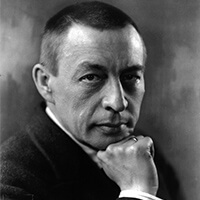

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) | Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Rachmaninoff, one of the outstanding pianists of his time, was a late example of the composer-virtuoso, a type whose peak years were in the nineteenth century. It is appropriate that the last of the great pianists should pay tribute to the great of the violinist-composers, Niccolo Paganini. In 1820 Paganini published a set of twenty-four Caprices for unaccompanied violin. Like Chopin’s Études, these were more than mere technical exercises. Their musical merit was sufficient to inspire such composers as Schumann, Liszt, and Brahms to use them as the basis for piano compositions. The twenty-fourth Caprice in A minor, with its theme-and-variations form, has been a particularly fertile source of inspiration for subsequent composers. Rachmaninoff wrote his set of variations for piano and orchestra in 1934.

Rachmaninoff, one of the outstanding pianists of his time, was a late example of the composer-virtuoso, a type whose peak years were in the nineteenth century. It is appropriate that the last of the great pianists should pay tribute to the great of the violinist-composers, Niccolo Paganini. In 1820 Paganini published a set of twenty-four Caprices for unaccompanied violin. Like Chopin’s Études, these were more than mere technical exercises. Their musical merit was sufficient to inspire such composers as Schumann, Liszt, and Brahms to use them as the basis for piano compositions. The twenty-fourth Caprice in A minor, with its theme-and-variations form, has been a particularly fertile source of inspiration for subsequent composers. Rachmaninoff wrote his set of variations for piano and orchestra in 1934.

The Rhapsody consists of a brief introduction, the theme, and twenty-four variations. It is somewhat unusual in that the first variation—a skeletal outline of the theme—appears before the statement of the theme itself. Although the Paganini theme serves as the thematic foundation, a subsidiary melody, the plainchant Dies irae (Day of Wrath) is also featured at times. This evocation of fire and brimstone appears most obviously in the seventh, 10th, and twenty-fourth variations. The variations go through many moods and styles—march, waltz, scherzo—culminating in the lush romanticism of the familiar eighteenth variation, derived from a melodic inversion of Paganini’s theme (that is, rising steps are transformed into equivalent falling steps and vice versa). This lyrical variation has been used in various movie and television soundtracks, including the films, Somewhere in Time (1980) and Groundhog Day (1993). The Rhapsody was also adapted as a ballet, based very freely on the life of Paganini. The 1939 ballet was a success, which pleased Rachmaninoff, and he wrote his Symphonic Dances in 1940 with choreographer Michel Fokine in mind. He played the piano version for Fokine, but both died before the idea got any further.

This is the BSO’s fifth performance of this work. Previous soloists were Allen Kindt (1973), Olivier Sorensen (1986), Lorin Hollander (1992), and Andrew von Oeyen (2014). The above program notes are based on those written for the 1992 performance by the late Jeffrey M. Edgmond, former BSO Principal Timpanist and Librarian.