Events

Classic Series

Fire & Ice

Saturday

Oct 15, 2022

7:30PM

Alberta Bair Theater

2801 Third Ave. N.

$15 - $66

Chee-Yun, violin

Jean Sibelius | Violin Concerto

Sergei Rachmaninoff | Symphony No. 2

Violinist Chee-Yun, whose flawless technique, dazzling tone, and compelling artistry have enraptured audiences on five continents, and the Billings Symphony takes on the turbulent and intense Sibelius Violin Concerto. After leaving the icy Nordic landscape, the orchestra continues with Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2. Enjoy every indulgent minute of this lush and expansive Romantic work.

Violinist Chee-Yun

CHEE-YUN | VIOLIN

Violinist Chee-Yun’s flawless technique, dazzling tone, and compelling artistry have enraptured audiences on five continents. Charming, charismatic, and deeply passionate about her art, Chee-Yun continues to carve a unique place for herself in the ever-evolving world of classical music.

A winner of the Young Concert Artists International Auditions and a recipient of the Avery Fisher Career Grant, Chee-Yun has performed with many of the world’s foremost orchestras and conductors. She has appeared with the San Francisco, Toronto, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, and National symphony orchestras, as well as with the Saint Paul and Los Angeles Chamber Orchestras. As a recitalist, Chee-Yun has performed in many major U.S. cities, including New York, Chicago, Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Atlanta. In 2016, Chee-Yun performed as a guest artist for the Secretary General at the United Nations in celebration of Korea’s National Foundation Day and the 25th anniversary of South Korea joining the UN. In 1993, Chee-Yun performed at the White House for President Bill Clinton and guests at an event honoring recipients of the National Medal of the Arts.

Her most recent recording, Serenata Notturno, released by Decca/Korea, is an album of light classics that went platinum within six months of its release. In addition to her active performance and recording schedule, Chee-Yun is a dedicated and enthusiastic educator. Her past faculty positions have included serving as the resident Starling Soloist and Adjunct Professor of Violin at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and as Visiting Professor of Music (Violin) at the Indiana University School of Music. From 2007 to 2017, she served as Artist-in-Residence and Professor of Violin at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Chee-Yun plays a violin made by Francesco Ruggieri in 1669. It is rumored to have been buried with a previous owner for 200 years and has been profiled by the Washington Post.

Get to know Chee-Yun in this interview with Laura Bailey for the Billings Symphony >>

PROGRAM NOTES

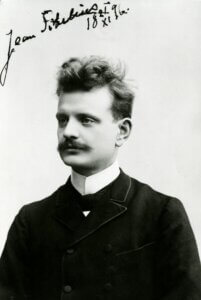

Jean Sibelius, courtesy Sibelius Museum

Jean Sibelius (1865–1957)

Violin Concerto

Sibelius consciously and assiduously studied and absorbed the musical and literary heritage of the Finnish culture and adroitly folded them into a unique personal statement. He was completely taken by the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, and early on his musical style reflected these cultural elements, from his melodic choices to the stories behind his tone poems. His symphonies are large soundscapes that surge and ebb, whose melodies often appear first as small kernels of a few notes whose significance is easily overlooked.

But, as the music unfolds and these bits of melody appear in a kaleidoscope of identities, they meld together into great torrents of themes. Sibelius was a master of orchestration, and most listeners easily accept the inevitable comparisons to the bleak, cold, primeval landscapes of Finland.

Sibelius’ violin concerto has certainly stood the test of time, and is one of his most-performed works, as well as being one of the most important violin concertos in the repertoire. It was composed in the period of his first two symphonies, and was first performed in 1904 in Helsinki (the performance was essentially a disaster—the violinist was not up to the task.)

In some ways, the piece would seem to be a contradiction. On the one hand it is infused with his signature dark, cold Nordic textures that seem to float impersonally over human trivialities. Yet, on the other, concertos by their very natures are often showpieces for a very real, single human being who plays musical material conceived to express that individuality. Pulling these disparate elements together would certainly seem a challenge, but Sibelius, on the whole succeeds quite well. After the ill-fated first performance he spent some time revising, and the concerto was performed to great acclaim in Berlin in 1905, with Richard Strauss conducting.

Several points are recommended to the listener. First, and it is rather evident, this concerto is really difficult! Sibelius began as a violinist, and with a player’s grasp of the violin’s capabilities, he laid down formidable technical challenges to the performer. Replete with double stops of all varieties (listen especially for the octave double stops at the end of the first movement), quick jumps from first to seventh position, and broken chords at very fast tempos, it is virtually a compendium of every difficult thing a composer might ask of a virtuoso violinist.

Especially impressive in the first movement is the passage wherein two of the soloist’s fingers execute a trill while the remaining two digits finger a melody on another string. The last movement has its impressive challenges, as well. An innovation is the long and important solo cadenza in the middle of the first movement that essentially functions as the development section. Relief from dark moods and textures, and brilliant technical challenges is found in the lyrical middle movement. Throughout the concerto be aware of the impressive imagination exhibited by Sibelius in his creation of almost unique tonal colors through an imaginative scoring for the orchestra.

(Excerpted from notes freely provided by William E. Runyan, PhD | © 2015)

OCt. 15, 2022 will be the fourth Billings Symphony program to feature the Sibelius. Prior to the full-length performances by David Kim (September 2007) and Peter Winograd (September 1992), 1979–80 MASO Young Artist, Kurt Sprenger, amazed our April 1980 audience with the opening movement.

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1957)

Symphony No. 2

Sergei Rachmaninoff, pictured in 1910

For several years following the success of his Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1901, Rachmaninoff was much in demand as a piano virtuoso, conductor, and composer. The workload became so severe that he decided to go into hiding for a time in Dresden, writing to a colleague, “I have escaped from my friends. Please don’t give me away!”

His time in Dresden was productive: in three years he composed his tone poem, The Isle of the Dead, and the famous Piano Concerto No. 3. And it was in this relative seclusion that Rachmaninoff finally returned to symphonic writing, starting work on the Symphony No. 2 in October 1906, completing it the following fall, and conducting the premiere in St. Petersburg on February 8, 1908.

Although the work was an immediate success, Rachmaninoff insisted that he really didn’t enjoy the experience of creating it—“the work became terribly boring and repulsive to me”—and vowed he would never again write a symphony. (He eventually relented, producing the Third Symphony 28 years later.)

The Second Symphony is a large work, closely descended from the symphonies of Tchaikovsky in its lavish orchestration and luxuriant rhetoric. Eric Carmen used parts of the third movement for his 1976 song, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again.” As Rachmaninoff’s music was still under copyright at the time—much of his music is now in the public domain—Carmen was made to pay royalties to the Rachmaninoff estate for the use of the composer’s music in both this song and the aforementioned “All By Myself.”

More recently, a section of the second movement was used several times in the 2014 film, Birdman, featured as part of the score composed by Mexican jazz drummer Antonio Sánchez.

Previous performances of Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony were in February 1975 (under the baton of Maestro George Perkins), March 2003 (Maestro Uri Barnea) and November 2009 (Maestra Anne Harrigan).